Chapter 4

Dispatching

and Other Technology

One of the things I looked forward

to in transferring back to the flatland was working with a more

professional dispatch system. In the Malibu region (which

included Topanga), dispatches occurred over County-owned

"land lines," telephone wires to each of the stations

from the Malibu dispatch center located at Fire Station 65.

The system could be unreliable (we

often suspected that a bird landing on a wire between Stations 65

and 69 could short-circuit our link with the outside world). Even

worse in my view, most of the dispatchers at Malibu had no

standard format for obtaining information from callers or

reporting alarm information to the stations.

Many times, we would waste time

interrogating the dispatcher, trying to get information about the

location or nature of an emergency we were being dispatched to.

As often as not, the dispatcher had gotten excited while talking

to the reporting party and failed to ask important questions. In

other cases, he would jot notes while taking information from a

caller and then be unable to decipher his own notes while

dispatching us. The system has since been shut down and merged

with the LA dispatch, but at the time it was a frustrating symbol

of the old "country fire department" that LA County

Fire Department had emerged from.

Station 7 was part of the

selective calling unit (SCU) network. Prior to 1956, the LA

County Fire Department had linked all of its stations with leased

telephone lines (each one of which was owned and maintained by

Pacific Bell Telephone Co. and priced on a per-mile-per-month

basis). Because of the far-flung nature of the department, its

annual phone bill was reported to be the second highest for any

user west of the Mississippi River. Furthermore, the system was

subject to failure in the event of storms or earthquakes.

The alternative was to create a

system that would dispatch by radio. To make it selective - so

that individual stations could be alarmed without all stations

being notified or disrupted - the selective calling units were

developed. By transmitting individual sets of two consecutive

tones to receivers that were tuned to activate only upon

receiving their respective two-tone signal, the system could

eliminate the need for expensive phone wires between the dispatch

center and each of the stations.

The receivers were on and awake 24

hours a day, but they would not activate the lights and audible

warning devices at a station until that particular station's two

tones sounded. A tone consisted of two or more

"frequencies," meaning audible or inaudible vibrations

at given frequencies, or cycles per second. The cycles-per-second

are measured as a Hertz (named after the guy who first discovered

the concept). Thus, a 60-Hertz signal will sound or measure

different than a 90-Hertz signal. A radio broadcasting at 154

Megahertz (referred to as VHF, or "very high

frequency") or 465 Megahertz (referred to as UHF, or

"ultra high frequency") will be inaudible to the human

ear unless it is modulated.

Many of the stations on the LA

dispatch network shared the same sound for the first of the two

tones. When that first tone would be sounded, numerous receivers

would perk up their electronic ears, so to speak, waiting for the

second tone. If the second tone did not contain the peculiar set

of frequencies that were programmed into a receiver, it would

lapse back into its waiting mode. It wouldn't trigger the lights

and claxon at its station unless and until it heard its own set

of second tones.

This explains why the buzzer

(claxon) would sound at station 51 almost immediately after the

second tone would sound. It took only an instant for the

station's receiver to recognize the tone, even though it

continued to broadcast for another second or two. In

multiple-station dispatches, additional two-tone signals would be

heard, but we would hear the entirety of the second tone for each

of those units or stations. Actually, at the physical sites of

those stations, the lights would go on and a claxon or other

audible warning device would sound instantly upon hearing its

second tone. However, since we were hearing the actual radio

broadcast of those tones from a distance, we would hear the

entire duration of both tones for the other stations, even after

their lights and devices were triggered.

A switch on the side of the SCU

console allowed the unit to "monitor" (meaning listen

to everything that was happening throughout the LA dispatch

area), or to "stand-by" (meaning that other alarm

activity and radio traffic could be muted until the specific SCU

was triggered). It would then remain on "monitor" until

re-set for "stand-by." Most stations remained on

"monitor" during daytime and early evening hours but

switched to "stand-by" after members started to

"sack out" (go to bed).

The only way the dispatch center

could know that its alarm had been received was for someone at

the station to verbally acknowledge over the air. Since each

station was a fixed broadcast site, they each required a license

issued by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Whenever

the FCC licenses a fixed broadcast site, it assigns call letters

to it. Usually, they consist of three letters and three numerals

(for example, KMA941 or KMG365).

FCC regulations require that

broadcasters identify their station with their call letters at

least once per hour if they are broadcasting continuously, or

upon each use if broadcasting intermittently. Thus, when Captain

Stanley received an alarm at Station 51, he would acknowledge to

the dispatch center ("Station 51") and comply with FCC

regulations ("KMG three six five").

In recent years, technology has

improved and selective calling units have been developed with

single-frequency tones. But when the LA County system was

developed, the relative sensitivity of receivers required that

multiple-frequency tones be used. This made the signals sound

much like a child playing at the keys of an out-of-tune organ. In

October 1971, Jack Webb asked musician/conductor Billy May to

come to LA County Fire Station 8, where filming of some World

Premiere scenes would occur.

While at Station 8, Billy May

heard the sounds of the SCU system. To a firefighter, it was just

background noise, but to a musical genius it was the foundation

for a musical theme. Thus, the original theme music for

"Emergency!" performed by Nelson Riddle and orchestra.

Anyway, back to the original

point, I was glad to be working in the LA dispatch system,

especially when Sam Lanier was on duty. As mentioned in "The

Emergency! Companion," Sam always maintained his

professional composure, never confused his role, frequently

thought "around corners" to assist field commanders,

and did it all with a cool baritone voice that never wavered so

much as a quarter-octave. All these attributes won him his role

as the voice of "Emergency!"

All the LA dispatchers were busy;

thus most of them were almost unflappable. Most important was the

fact that we usually got all the information we needed with the

original broadcast. Most often, it was clear and concise and we

could be "out of the barn" (leaving the station

en-route to an emergency) in a minute or less.

Midnight

at the Playboy Club

During the first half of 1970, I

was studying for the final exams for my last three law school

classes, and I was continuing to work on my fire company

supervision textbook. Since my home was filled with all the

disruptions of noisy little boys, most of my off-duty studying

occurred at the LA County Law Library or at my parents' home in

Monterey Park. The studying had become intense, in anticipation

of the bar exam. I looked forward to coming to work, continuing

the pre-fire planning, fire prevention inspections and training.

Amidst it all, we had a lot of

fun; I remember going off duty at the end of numerous shifts with

my stomach muscles hurting from laughing so much in the prior 24

hours.

Everybody knew that the Battalion

Chief eligibility list was about to expire (they were only valid

for two years). Thus, a promotional process would be held

sometime during 1970. It was in the back of my mind, but I knew I

wouldn't be able to study for it till after the bar exam.

blackjack online juego.

At that time, promotional exam

processes for Captains and Battalion Chiefs consisted of three

parts: a written exam, an oral interview, and an "appraisal

of promotability" (or "AP"). The AP was derived

from a very subjective process. All of the department's chief

officers would gather at the training center auditorium.

One-by-one, the names of candidates for promotion would be posted

at the front of the room.

Usually, a candidate's current

chief officer would propose a score for him (between 70 and 100).

In some cases, there would be no comment and the original AP

score would stand. In other cases, if a candidate had somehow

created a bad impression with a chief officer, that chief would

offer his negative impression. Strongly held views would surface

and peoples' reputations would be ravaged -- with no opportunity

for them to defend themselves.

Even though the process was

supposed to be secret, leaks would occur. For example, a chief

officer shared with me a comment that was made when my name came

up during the Captain's exam AP meeting. Reportedly, a particular

chief officer issued a warning to the assembled group: "This

guy someday will be the chief of the entire department, but he'll

get there over the dead bodies of everybody who works for

him." I never learned who had made that remark and, to this

day, I'm not sure what inspired it. Whatever the intent or

motivation, it didn't have a negative effect. My AP score for

that exam was 100.

I suspected that several of the

ranking chief officers in the department were intimidated by my

education. They and others, I suspected, were beginning to view

me as a threat to their own career plans. I wondered how that

would affect my score if I were to compete for the Battalion

Chief position.

Destiny intervened on the early

morning of June 3, 1970. At Station 7, we had had a busy day,

with lots of alarms for more-or-less routine events (trash fire,

car fire, an elderly lady having difficulty breathing, a couple

of false alarms, and two or three cancelled responses into

Station 8's district). About 11:30pm, I went to bed. The next

morning, I was scheduled to drive my wife and kids to Palm

Springs for a swim meet, so I had arranged for the on-coming

Captain to arrive early.

At 12:05am, the alarm rang. I had

just lapsed into deep sleep. Before the bell stopped ringing, I

was on my feet, getting into my turnouts, but I had trouble

clearing my head. Before I could get to the SCU console on the

apparatus floor, the dispatcher broadcast the message. My mind

was still fuzzy and I wasn't sure what I had heard. I picked up

the microphone and asked for a repeat of the dispatch

information.

"Fire at the Playboy Club,

Sunset and Alta Loma. Numerous calls. Station Seven, Station

Eight, Engine Thirty-eight, Engine Fifty-eight, LA City Engine

Forty-one, and Battalion one responding." That got my

attention. As I climbed aboard Engine 7, Engineer Danny Deaver

punched the throttle on our "Toyopet Crown" and we

started up the Hancock Street hill.

The "Toyopet" label was

a term of derision for the 30 or so cut-rate pumpers that had

been purchased by the County in the late 1950's. Division Chief

Byron Robinson had cut a deal with the Crown Coach Corporation to

build the pumpers for about 15 percent less than the standard

1,250 gallon-per-minute Firecoach. The lower priced vehicles

would be rated at 1,000 gallons per minute, and they would be

powered by a 580 cubic inch Waukesha six-cylinder engine, rather

than the standard 935 cubic inch Hall-Scott.

About the time the first of these

new pumpers were being delivered, the Japanese Toyota Motor

Company was trying to introduce its cars to the American market.

The top-of-the-line Toyota was labeled the "Toyopet

Crown." It was an ugly car and not well made. In a highly

publicized marketing campaign, the president of Toyota was to

drive a Toyopet Crown sedan from the East Coast of America to the

West Coast. The journey was never completed. The car broke down

almost daily and each mechanical mishap was reported in the

media.

LA County Fire Department

personnel were accustomed to fire apparatus powered by the big

Hall-Scoots. They had a deep, throaty sound, a fairly wide power

range, and plenty of low-RPM torque for going up hills. The

Waukesha-powered pampers, by contrast, had a tinny pitch to their

exhaust sound, and they operated at higher RPMs, which made them

sound like they were straining (which they were). When confronted

by a hill, they would quickly slow to a crawl.

It wasn't long before some LA

County firefighter put two-and-two together and matched the

reports about the unreliable Toyopet Crown limping across the

U.S. to the underpowered Crown fire engines that were being

delivered to his fire department. The "Toyopet" label

stuck to all of Chief Robinson's discount fire engines until all

of them eventually were re-powered with diesel engines. Chief

Robinson detested the label and would become almost apoplectic

whenever he heard someone utter it.

Unfortunately, in 1970, Engine 7

was a Toyopet and, as it crawled up the Hancock Street hill, I

could see a big glow in the sky in the direction of the Playboy

Club. I picked up the microphone and instructed the dispatcher to

notify all responding units that we had fire and smoke showing.

At LA Headquarters, Ed Gussman broadcast the notification with

the calm, cool manner of an experienced, professional dispatcher.

When we reached the top of Hancock

Street and turned right on Holloway, the engine picked up speed

and the glow in the sky got brighter. I pulled the pre-plan file

from its place under the pumper's dashboard, but I never really

needed it. We were very familiar with the building (which was

non-sprinklered) and our water resources (which were almost

limitless).

We turned from Holloway onto Alta

Loma and started up another hill. The Toyopet again slowed to a

crawl as Danny dropped back to a lower gear and the little

Waukesha powerplant sounded as though it might jump from its

motor mounts. A short distance after we started up the hill, the

fire came into view.

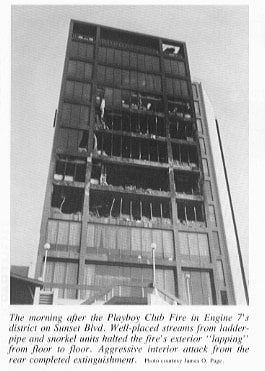

The Playboy Club was a ten-story

building that was perched on the side of a hill. The front of the

building faced Sunset Boulevard and that level of the building

was the second floor. The backside of the building, which we were

approaching, was mostly glass -- to accommodate a view that

stretched all the way to the Palos Verdes Peninsula and the

ocean.

The building essentially was a

series of vertical concrete columns and horizontal lightweight

concrete slabs, wrapped with aluminum frames that held 4' x 8'

panes of tinted 1/4" glass in place. The Playboy Club

occupied floors 1 through 3. Floors 4 through 9 were divided in

the middle by a central hallway constructed of one-hour

fire-rated wallboard and fireproof doors. These floors were

rented to musician Vic Damone, Ross Bagdasarian (aka "David

Seville," creator of "Alvin the Chipmunk"), and

other tenants, most of whom were associated with the

entertainment industry. The tenth floor was Hugh Hefner's

penthouse (prior to his purchase of the Playboy Mansion).

As we approached the fire, we

could see that floors 3 and 4 were fully involved, with flames

from those floors reaching up the backside of the building toward

the upper floors. I told Danny to take Engine 7 to the front door

of the building on Sunset. That would be our command post. As we

continued to crawl up the hill, just as we passed the backside of

the building on our way to the front door, the entire expanse of

fifth-floor windows on the back side fell from their frames and

crashed to the roof of the parking structure 50 feet below. With

that, the fire entered all of the offices on the backside of that

floor.

I knew that this would be one of

the biggest challenges of my career. I had long preached that

command of a fire was an acting performance of sorts. The people

on scene, those who monitored the radio transmissions during the

emergency, and those who later listened to the radio tapes

(during a post-incident critique) would become harsh judges of

the incident commander's performance. Not so coincidentally,

however, the best performances of incident command inevitably

produced the best outcomes on the fireground.

The LA County Fire Department had never

before experienced a major high-rise building fire. Normally, an

event of that magnitude quickly would fall under the command of a

chief officer. But West Hollywood was a geopolitical island,

surrounded by the cities of Los Angeles and Beverly Hills, each

of which maintained their own fire departments. Our fire

department had assigned the West Hollywood and Universal City

islands to Battalion 1, which was headquartered at Station 38, a

30-minute drive from the Playboy Club - even with lights and

siren.

The LA County Fire Department had never

before experienced a major high-rise building fire. Normally, an

event of that magnitude quickly would fall under the command of a

chief officer. But West Hollywood was a geopolitical island,

surrounded by the cities of Los Angeles and Beverly Hills, each

of which maintained their own fire departments. Our fire

department had assigned the West Hollywood and Universal City

islands to Battalion 1, which was headquartered at Station 38, a

30-minute drive from the Playboy Club - even with lights and

siren.

Our Battalion Chief was

"Whitey" Ardinger and I heard him on the air,

acknowledging my initial on-scene report.

I knew that he was a very competent

fireground commander and I looked forward to his arrival on

scene, but my competitive instincts were telling me to get the

fire knocked down before the chief arrived - without hurting

anyone.

I knew that he was a very competent

fireground commander and I looked forward to his arrival on

scene, but my competitive instincts were telling me to get the

fire knocked down before the chief arrived - without hurting

anyone.

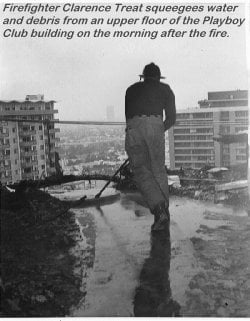

We stopped the upward progression

of the Playboy Fire at the 8th floor. The full report on the

event could be book-length. There were some superb performances

by a lot of people, and there was a lot of luck involved.

Twenty-nine minutes after we received the alarm, I reported to LA

Dispatch that the fire was knocked down (just as Chief Ardinger

arrived at scene).

Less than a month later, I

graduated from law school. A few days after that, I gave a report

on the Playboy Fire at a meeting of all the department's chief

officers. Afterwards, several chief officers told me I was a

little too polished, that I had made some of the older chiefs a

little uncomfortable.

The

California Bar Exam

At the time, I was almost totally

immersed in a bar review course; the bar exam was scheduled for

August. Thus, I was relieved to learn that the fire department's

Battalion Chief exam, also set for August, would not include a

written test. It would consist only of an oral interview and the

Appraisal of Promotability.

The bar exam was three days of

sheer torment. Since I was a typist, I was assigned to join 300

or so other examinees with typewriters at the Glendale Civic

Auditorium. The sound of that many typewriters, all furiously

hammering out answers to the essay-type questions, was

distracting at first. After awhile, however, the background noise

became barely noticeable as every one of my available brain cells

was focused on the exam. At the end of the third day, when it was

finally over, I was physically and emotionally depleted. In the

parking lot, I got into my Ford station wagon and immediately

drove over a curb.

In the weeks after the bar exam,

for the first time in thirteen years, I was able to give all my

attention to my family and my fire department job. It was

difficult to adjust, and my nervous energy continued unabated.

For a lot of reasons, my wife and I had lost the ability to

communicate well with each other. We both needed some time to

wind down and get reacquainted but I had used up all my vacation

time and holidays to finish school and study for the bar exam.

The boys were 13, 9 and 6, they

were typically rowdy and rambunctious, and involved in

competitive age-group swimming, so there was no real quiet time

at home. Instead of working on my relationship with my wife and

family, I retreated to my office at home and finished writing my

fire company supervision textbook.

The bar exam results came in

November, as I recall. I was home when they arrived in the mail.

My hands shook as I opened the envelope. "We regret to

inform you......," the letter said. I was devastated. Within

an hour or two after getting the bad news, I was analyzing why I

had failed. It was no mystery, really. A law professor once told

me, "the law is a jealous mistress." I had cheated on

that jealous mistress.

The Playboy Fire and its

aftermath, my preoccupation with the Battalion Chief exam

process, and trying to write a book while studying for the bar

were, in essence, arrogant disregard for solid advice. I had

believed I was different. I'd been skating through exams my whole

adult life, and I thought I'd skate through the bar exam. I had

nobody to blame but myself. Within 24 hours, I was plotting a

study program that would prepare me for the next exam, to be held

in March 1971.

Copyright 1998,

James O. Page

CHAPTER 5

The LA County Fire Department had never

before experienced a major high-rise building fire. Normally, an

event of that magnitude quickly would fall under the command of a

chief officer. But West Hollywood was a geopolitical island,

surrounded by the cities of Los Angeles and Beverly Hills, each

of which maintained their own fire departments. Our fire

department had assigned the West Hollywood and Universal City

islands to Battalion 1, which was headquartered at Station 38, a

30-minute drive from the Playboy Club - even with lights and

siren.

The LA County Fire Department had never

before experienced a major high-rise building fire. Normally, an

event of that magnitude quickly would fall under the command of a

chief officer. But West Hollywood was a geopolitical island,

surrounded by the cities of Los Angeles and Beverly Hills, each

of which maintained their own fire departments. Our fire

department had assigned the West Hollywood and Universal City

islands to Battalion 1, which was headquartered at Station 38, a

30-minute drive from the Playboy Club - even with lights and

siren. I knew that he was a very competent

fireground commander and I looked forward to his arrival on

scene, but my competitive instincts were telling me to get the

fire knocked down before the chief arrived - without hurting

anyone.

I knew that he was a very competent

fireground commander and I looked forward to his arrival on

scene, but my competitive instincts were telling me to get the

fire knocked down before the chief arrived - without hurting

anyone.